Buscar

Director: Froilán Meza Rivera

redaccion@cronicadechihuahua.com

La Crónica de Chihuahua - Relatos urbanos, ciencia, cultura y noticias.

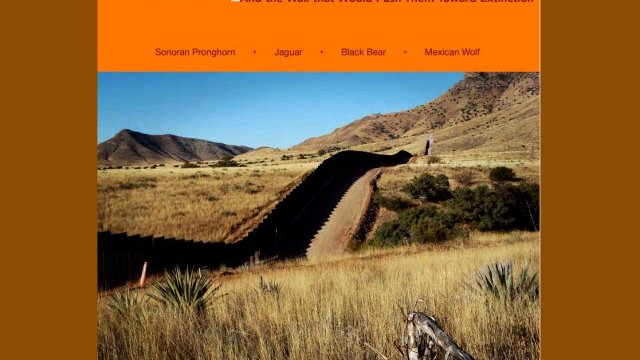

Four border-crossing species on the brink because of the Wall

MEXICAN WOLF, along with the black bear, the jaguar and the Sonoran pronghorn are amongst the major species that will result as a victim of -both- the current and the proposed Trump's Wall.

La Crónica de Chihuahua

Noviembre de 2017, 19:30 pm

Wildlands Network has published a new report, under the name "Four Species on the Brink- And the Wall that Would Push Them Towards Extinction", that remarks the potential impacts on the black bear, the Mexican wolf, the jaguar and the Sonoran pronghorn, as a result of the border wall, both the current and the psoposed one.

Following, we present the part corresponding to the Mexican wolf.

Expected effects of border wall:

• Blocking of dispersal corridors preventing genetic interchange between recovering ppulations in Mexico and the U.S., leading to populations at greater risk from local extinction.

What you need to know:

Mexican wolves are the most threatened subspecies of gray wolf in the world. Extirpated in the U.S. as a result of aggressive extermination campaigns during the last two centuries, wolves are only recovering now thanks to a binational reintroduction program. There are currently two semi-isolated populations, one in the region designated as Mexican Wolf Experimental Population Area (MWEPA) in southern Arizona and New Mexico and one in the Sierra Madre Occidental in Chihuahua and Sonora, Mexico.

Mexican wolves, despite their smaller stature when compared to other subspecies, can still travel huge distances and are constantly seeking new territories to establish good hunting grounds and safe dens, away from human disturbance.

What’s being done:

The Mexican wolf recovery program is a binational program involving several federal and state agencies of the United States and Mexico as well as breeding centers, veterinaries and field experts. It is cemented in nearly 30 years of international collaboration and keeps a captive population as genetically diverse as possible while advancing releases into areas deemed suitable in both countries. Animals released in any given site might have been born in either country and are selected based upon to how their genetic traits contribute to the overall goals of the program. Releases in New Mexico, Arizona, Sonora and Chihuahua and the reproduction of the individuals released have resulted in an overall wild population of at least 141 individuals. The USFWS recently issued a revised Recovery Plan, which focuses on the need to establish two populations of the species –one of them in Mexico– potentially connected by habitat good enough to facilitate gene-flow between them. Comments from experts on this draft plan, including those submitted by Wildlands Network, call for an increase in the target number of populations and the connectivity between them.

MEXICO collaborates in the captive breeding program and in 2011 started its own reintroductions. To date it has released 41 wolves in Sonora and Chihuahua and has managed to establish a population of approximately 28 wild wolves. In 2014 a pair of released wolves in Chihuahua had a litter of five pups, marking the first wild births of the species in Mexico in more than 30 years. The pair went on to produce two more litters in subsequent years.

Mexican scientists are currently evaluating the potential for additional reintroductions in the southern Sierra Madre Occidental. The same program that compensates for cattle losses due to jaguar predation covers losses from proven wolf predations, and landowners collaborating in wolf reintroductions receive financial incentives for managing their lands for conservation.

Border Crosser

In 2016, a female was born in a breeding facility near Cananea in the state of Sonora, Mexico. She was fitted with a collar and, in October of the same year, released in the neighboring state of Chihuahua, 90 miles from the international border. Known by wolf managers as f1530, and named Sonora by wolf advocates, she then traveled north. Her collar last located her 21 miles south of the border on Valentine’s Day, 2017. On March 19, she was sighted in Arizona, and a week later she was captured by an Interagency Field Team in charge of the species’ on-the-ground management, to be taken to a breeding facility, pending a decision on her future.

Sonora showed a wild courage in traveling through the rugged terrain of the borderlands, undeterred by highways and other obstacles in her search for a family.

What’s at stake:

Recovery of such a wide-ranging species necessarily requires trans-jurisdictional collaboration as well as a foundation of goodwill and trust between partners. A recovery, decades in the making, could be more threatened than ever if limited by an impenetrable border wall resulting from a lack of long-term planning for sustainable, cross-border populations. Despite veterinarians’ best efforts, the best strategy to prevent genetic issues detrimental to a species’ survival remains establishing several wild and connected populations. With Mexican wolves already facing problems associated with their shallow gene pool, it is imperative that populations in the wild

be allowed to continue the dynamics of natural selection unimpeded by infrastructure that could preclude gene flow between packs.

©2024 La Crónica de Chihuahua - Relatos urbanos, ciencia, cultura y noticias

La Crónica de Chihuahua es un diario independiente, enfocado a describir las singularidades y la cotidianidad de la comunidad chihuahuense.